In the first two articles, we focussed on rhythm. In part 3 of this production basics series, we are getting into melodic territory. But before we get to work on creating melodies we first have to talk about the system behind melodies. Let’s talk about scales. Mainly the Major scale.

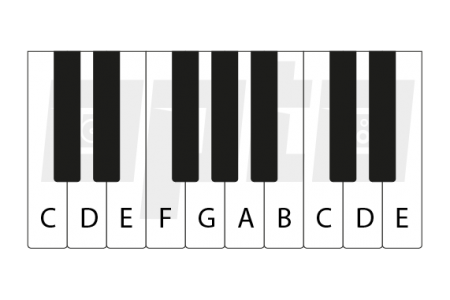

A melody is made of notes. In western music, we basically only have 12 notes. But those notes can be arranged in endless combinations to come up with a unique song every time. If you look at a piano you will see that its keys are organized in a specific pattern. Some white notes have black notes in between while others don’t. All notes on a piano keyboard repeat themselves after 5 black notes or after 7 white notes.

The White Keys

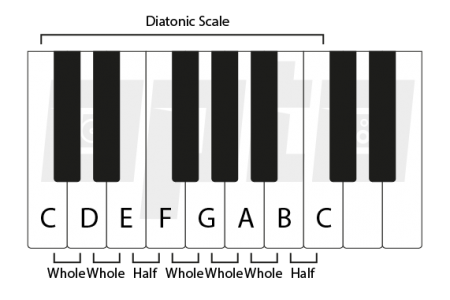

The white notes are called the natural pitches and each has it’s own name starting from A and ending on G. A piano key that is adjacent to another is called a half step and if you skip one adjacent key you will get a whole step. Most western pop music doesn’t really make use of all 12 notes in a song. Most of the time only 7 notes are used. This is called a diatonic scale.

Diatonic Scale

A diatonic scale is made up of a pattern of 5 whole steps and 2 half steps. There is one place on the keyboard where this scale naturally occurs. That is if you play all the white notes, you are playing a diatonic scale. Now if you start on C and play all the white notes until the C above you will hear the C Major scale.

Let’s look at the keyboard for a moment. If you start on C and move to the next white note D you’ll notice that there is one black note in between.

This is a whole step. If you move from D to the next note called E you will have another black note in between and thus this is another whole step. If we continue from E to F, there is actually no black note in between so we get a half step. Continuing this pattern we’ll see whole steps again with the exception to the last keys from B to C which is a half step.

The whole pattern is as follows:

C (Whole) D (Whole) E (Half) F (Whole) G (Whole) A (Whole) B (Half) C

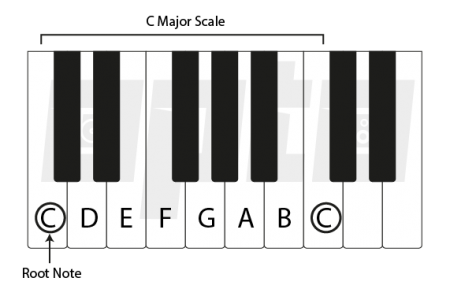

This pattern can be applied to all twelve notes to create a major scale. The note you start on is called the root note. So if we start on C the root note is C and so the scale will be called the C Major scale. The C Major scale is the only major scale that doesn’t have any black keys. We haven’t talked about the names of the black keys yet so let’s start by doing that.

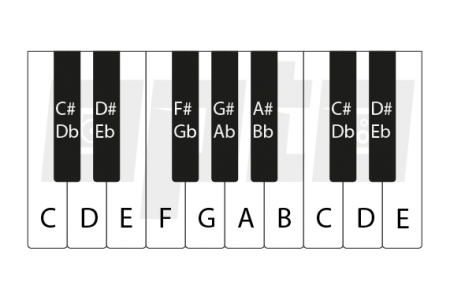

The Black Keys

Because the black keys are in between the natural white notes you can start on a white key and move up to the right (higher pitch) or down to the left (lower pitch). The black keys are indicated by their adjacent white key and get a # or sharp if it’s above the white key and a b or flat if it’s below the white key.

So if you take the white key G for example and move up to the closest black note, that note is now called G# or G-sharp. If you move down to the closest black note starting from G you will get Gb or G-flat.

This means that every black note actually has 2 names! The black keys are actually called enharmonic notes. So how do we name them? There’s actually a simple rule for that. The rule is that we can only use one letter per scale. So if we use a G and want to use a note one-half step higher, we can’t name it G# because G is already used. The only option would be to flatten A to Ab as it sounds the same as G#.

Some Examples of Major Scales

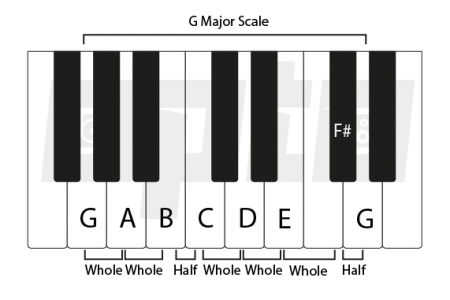

Let’s say that we wanted to create a G Major scale. To find the right notes of this scale we start on G and apply the diatonic scale pattern of whole steps and half steps:

G (Whole) A (Whole) B (Half) C (Whole) D (Whole) E (Whole) F# (Half) G

E to F is originally a half step, but since we need a whole step to follow the pattern we need to add one half step extra to raise F to F#. We can’t name it Gb because G is already used.

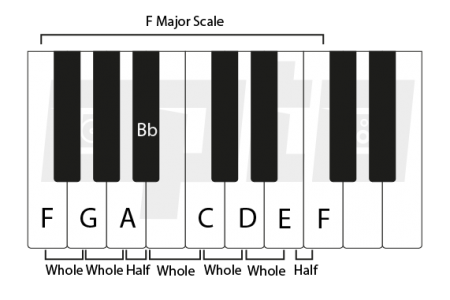

Let’s look at another scale, this time we’ll start on F:

F (Whole) G (Whole) A (Half) Bb (Whole) C (Whole) D (Whole) E (Half) F

If we stayed at the white keys then the interval between A and B would be a whole step, but according to the pattern we need a half step here so we flatten the B to Bb as we already used A and can’t use it again.

By following the diatonic scale pattern of whole steps and half steps we can figure out which notes are sharp and which notes are flat for all 12 keys. The fun thing about keys is that you can play any note in a scale and it will always sound good. 9 out of 10 pop songs only use one key so by knowing some basic music theory rules we make our life a whole lot easier when trying to figure out melodies later on.

Today we’ve learned something about note names and the major diatonic scale. In part 4 of this production basics series, we’ll talk about another type of scale: the minor scale. We’ll also dive into intervals and their names.