This is the first part of a series about music production aimed at beginners. Learning to write and produce your own tracks from scratch is a tough but very rewarding journey. To become an expert in the craft of music production you need to start with the basics. One of the fundamental parts of music production is music theory. I promise to make it as simple as possible but at the same time, I want you to really understand the fundamentals. By understanding the basic elements of music theory you will eventually become a better and more versatile producer. The goal is to provide you with enough information to get started making beats on your own without diving too deep into all the tiny little details. With that all said and done, let’s start with the basics of rhythm.

The basics of rhythm?

Rhythm is the most fundamental part of music theory, without it, there wouldn’t be music. It’s like the heartbeat of a musical composition. Rhythm makes us want to dance. It exists of fundamental energy called pulse. The pulse is the underlying guide that every rhythm is made up of. Finding the pulse is easy. Just tap your feet or clap along with a piece of music and you will find the pulse. The pulse is the driving force behind the music, like a motor, always moving forward.

A pulse can be divided up into terms like beats, measures, and time signatures. If you count along to a piece of pop music you will find that you can count up to four before the pulse starts to repeat itself. Rhythm is all about repetition. If you count along (1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4…) then every count is called a beat. After 4 beats the pattern repeats itself. This pattern of 4 beats is called a measure or ‘bar’. Since one bar has 4 beats, a pattern of two bars has 8 beats in it and a pattern of 16 bars is made up of (16 x 4 =) 64 beats.

Relative time v.s. absolute time

Some songs are faster than others, but how exactly is time measured in music? Think about a clock. A clock gives us absolute time. Every rotation of the earth around its axis is called one day. Each day is divided into 24 hours. 1 hour is divided into 60 minutes and a minute is again divided into 60 seconds. One second always takes the same amount of time, that is why we can call it absolute.

In music, however, time is not absolute but relative. We can have two pieces of music of exactly 1 minute long, but one piece can play faster than the other. So how does this work? Let’s introduce a new term called Beats per minute or BPM.

As the name implies, the BPM is a number that gives us a number of beats in 1 minute. If we have a song of 60 BPM, one beat would last for exactly 1 second. (60 seconds / 60 beats = 1 second). When we have a song with a BPM of 120, each beat would last 0,5 seconds (60 / 120 = 0.5). This song would be twice as fast as the song that only had 60 beats per minute because you would need to count 120 beats in one minute instead of 60.

Note values

So far we have introduced beats. But there is more to rhythm than just beats. Beats are like the heartbeat of music (a heartbeat is also measured in BPM by the way). But we can divide those beats in smaller values to create other note values. We’ve seen before that doubling the BPM will result in the music playing twice as fast. The tempo, or BPM, of a song, usually stays the same from beginning to end so how do we increase the speed of rhythm without changing the tempo? In pop music one bar is made up of 4 beats, in other words, we can divide a bar in 4 to indicate a beat. If you divide something into 4 parts you get a quarter. Tie the word ‘note’ to it and you get a quarter note.

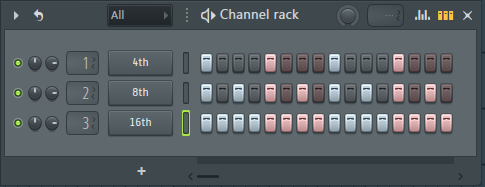

Now, what if we divide this quarter note in half again? Half a quarter is 1/8th and so the name of this note length is called an eight note. Since we have 4 beats or quarter notes in a bar, we can say that 8 eight notes will fit into one bar as well! Of course, we can go further than an 8th note by dividing the 8th note in half yet again. This creates a sixteenth note of which 16 will fit into one bar.

Note length

One quick note about note length. Percussive sounds like kick, bass, and hi-hat have a set note length. If you strike a drum it simply decays over time. Other instruments, however, like a violin or flute do allow you to influence the length of a note. The longer your breath, the longer the note you can make with a flute.

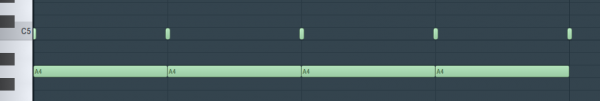

A traditional step sequencer like in the picture shown above, therefore, doesn’t have any note length. The channel rack from FL Studio allows you to modify the start point of a sound but if you open up the piano roll you’ll see that all note lengths are infinitely short. They don’t have a duration.

Any other instrument will sound as long as the note is playing. In traditional notation, note values are therefore linked to note duration. One 8th note is exactly 1/8th of a bar long. One 16th note is exactly 1/16th of a bar long.

Time signature

There is one last thing we need to talk about in order to understand the basics of rhythm. This has to do with the relationship between beats and measures. In 90% of pop music we can count up to 4 and the pattern repeats itself. But not all music is made up of patterns of 4.

Take the classical Waltz for example. This is a dance and is counted until 3 (1,2,3, 1,2,3…). Because in this case, the pattern repeats itself after 3 beats, a measure is now made up of 3 beats instead of 4. In music theory, this is visualized as a fraction: ¾. The top number of the fraction, the numerator, indicates the number of beats, while the bottom number, the denominator, indicates the note value that represents one beat.

In a ¾ time signature, the 4 in the denominator represents a quarter note, thus we have 3 quarter notes in one bar. In the more common 4/4 time signature we get 4 beats with a size of 1 quarter note per bar.

To summarize

You probably never thought that being able to count to 4 is so useful right? In part 2 we will expand on the basics of rhythm by talking about other note lengths such as triplets and dotted notes, shuffle, groove, velocity, and more!